(September 19, 1880 – July 1, 1973)

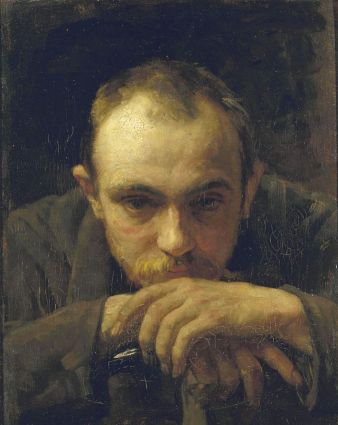

Clarence Kerr Chatterton, the creator of Vassar’s Applied Art (studio art) program, was born in Newburgh, NY, on September 19, 1880, to Charles L. Chatterton, a lawyer born of English parents, and Julia Lendrum Chatterton, the daughter of a mayor of Newburgh. Although they allowed him to study art in school, his parents did not support his desire to become an artist. However, from1900 to 1904 he attended the New York School of Art, where he was taught by Robert Henri, William Merrit Chase, and Kenneth Hayes Miller. His fellow students included George Bellows, Gifford Beal, Guy Pene DuBois, Rockwell Kent, and Edward Hopper, with whom he shared studios.

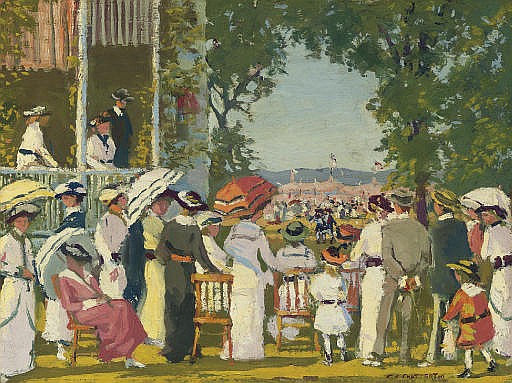

Chatterton’s recognition as an artist grew steadily. In 1910, his paintings were included in an exhibition with Henri’s group at the fashionable Macdowell Club, housed at that time in the Metropolitan Opera House. The same year his painting “Snow Clad Town” was exhibited in South America. In 1913, Chatterton won the Isidor Prize for best work in watercolor at the Salmagundi Club in New York City, where he was a member.

Chatterton returned to Newburgh and married Margaret Antoinette Meakim, a musician, in January 1915. In the fall of that year Oliver S. Tonks, the chairman of Vassar’s art department, hired Chatterton to teach painting and applied art, making Chatterton one of the first artists-in-residence at any college in the United States. Chatterton’s arrival at Vassar coincided with a period of significant change, exemplified by the construction of Taylor Hall and the inauguration of President Henry Noble MacCracken, who would become a good friend to the artist.

His studio art classes, held on the fourth floor of Taylor Hall and later in Ely Hall, were the first of their kind at the college since the death of the college’s first art professor, Henry Van Ingen, in 1898. A member of the college’s founding faculty, Van Ingen had taught both the history of art and studio work, and Chatterton’s instruction was planned to correspond to the styles and subjects taught in the art history department. In the beginning, his studio classes were only supplemental to the art history courses and were not accredited on their own, but he successfully convinced the college and its trustees in 1919 to grant separate academic credit for his painting classes.

“Chatty,” as he was nicknamed by his students, believed that drawing from the live model was essential for his art students. Both male and female nude models were brought in for the students to draw from, and initially a chaperone was required during these drawing sessions. In addition to drawing and painting from life, his classes included composition, landscape, portrait, oil, watercolor, and sculpture. Offering the kind of classes and instruction found in art schools Chatterton’s studio classes became the model for many similar departments at other liberal arts colleges and universities.

The faculty also benefited from having an artist-in-residence on campus. Every Tuesday night Chatterton held life-drawing sessions for fellow professors in his home. A group of about 12 met every week to receive Chatty’s criticisms and suggestions. In the summertime he held a class in Ogunquit, Maine, where for 50 dollars tuition students could learn landscape sketching and painting. Along with his friend and fellow painter Edward Hopper, Chatterton spent most of his summers in Ogunquit and Monhegan, Maine, drawing on the locale for many of his paintings.

In 1925, the Wildenstein Gallery offered Chatterton his first one-man exhibition and her presented a second exhibition there two years later. He was susequently associated with the Macbeth Gallery in New York, where solo exhibitions were mounted in 1929, 1931, 1934, and 1936. In 1936, his work was included in the first National Exhibition of American Art exhibit at Rockefeller Center

As a painter, Chatterton was a realist who focused on small town America. He painted lived-in scenes, shaded streets, river traffic, and the ordinary surroundings of fishermen. He believed that, “an artist should express himself with as little fuss as possible in a frank, uncompromising manner. I paint sunlight, blue skies and houses because I like them.” In 1934, the New York American described Chatterton’s approach:

“Mr. Chatterton’s point of view is characterized by a certain serene enjoyment of actualities that amounts to a philosophy of life. His pictures of New England villages and streets, of meadows and trees and white meeting houses induce something of the same reaction one gets from reading Thoreau or Emerson. His manner of setting down his reactions has the integrity of his point of view which is characterized by directness and candor”

And in 1931, The New York Times commented, “Mr. Chatterton sees the white houses, the tall elms, and dusty streets of New England towns as the important things in a picture… this sentiment of place is supported by a strong, forthright technique…Chatterton must be reckoned among the indigenous—and important—American painters.”

In later life, Chatterton recalled that when he was offered the post at Vassar, Robert Henri, his old art teacher, had commented, “I don’t know much about Vassar, but I think it’s a pretty good place, and if you do decide to go up there, I’d stay just about a year, possibly two.” Chatterton added, “Most of my friends thought, ‘That’s the end of Chatterton as a painter,’ but a few years later many of them were searching for similar positions. I stayed at Vassar for 33 years because I just fell in love with the place.” He retired in 1948, having taught some 3,000 students.

After retiring, Clarence Chatterton remained in Poughkeepsie and continued working as an artist. He died on July 1, 1973. He was 92.