(August 18, 1909 — April 19, 1978)

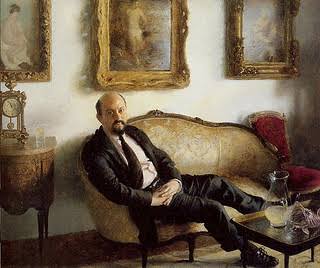

John Koch was a self-educated artist. Born in Toledo, Ohio and raised in Ann Arbor Michigan, he attended local public schools, graduating from high school in 1927. As a teenager, he studied charcoal drawing—his only experience with formal art instruction. In 1928, Koch traveled to Paris where he remained until 1934. The young American Midwesterner taught himself to be an artist in the galleries of the Louvre, modeling his practice on painstaking observation of the museum’s collection. From his earliest years, Koch was primarily figure painter, supporting himself in Paris with portrait commissions. Through the decades of the 20th century, as abstraction became the defining mode of contemporary art, Koch remained defiantly committed to a rigorously realist style. Faithfulness to what the eye sees suited the tastes of Koch’s society patrons who sought out his skill as a portraitist. It was, as well, a sincere expression of his personal beliefs. Koch’s realism, expressed in a visual language related more to the past than to even the objective art of the twentieth century, bedeviled critics of the contemporary art scene, defensively dedicated as they were to the project of convincing the public at large of the sole legitimacy of abstraction as a way of making art.

Dora Zaslavsky, Koch’s wife, was the child of eastern European immigrants, brought to the United States as an infant. A piano prodigy from the tenements of East Harlem, she attracted the notice of Janet Schenck, the founder of what became the Manhattan School of Music. Zaslavsky was among the school’s first graduates and served as a revered piano teacher there from 1926 until she retired in 1986. By the time Koch returned to New York from Paris, he had already shown his work in Paris group exhibitions. In 1934, he courted Zaslavsky, who was in the process of ending a brief first marriage. The couple married in 1935, the same year in which Koch had his first solo gallery show in New York. In 1939, he was the last artist taken on by John Kraushaar, owner of the estimable Kraushaar Galleries before he passed the business on to his daughter, Antoinette. Koch remained with Kraushaar throughout his life, withnumerous solo shows capped by a memorial exhibition in 1980, and a posthumous one-man show in 1996.

Portrait painting subsidized the lifestyle that allowed Koch to follow his own muse and produce the body of work for which he is best known: carefully composed paintings of interiors, sumptuously detailed, and comfortably furnished, where cultured people gathered to intermingle surrounded by music, art, and freely flowing cocktails. Koch’s meticulous realism brought him a national reputation, at the same time it elicited criticism for a perceived lack of evolution during a career that paralleled the transition in art from postwar abstraction to the counterculture of the Vietnam era. Koch’s work is probably best understood as intensely personal, almost hermetically sealed within the walls of his Upper West Side apartment, studio, and, occasionally, his home on Long Island. His interior scenes, alive with people, often recognizable friends, also served as an opportunity for him to exercise his impressive skills as a painter of still life. The Koch home abounded in the material objects of a life graciously lived: art, sculpture, musical instruments, fine furniture, plants, flowers, and food and drink proffered on porcelain and silver. These scenes, often focused on musical performance, are closer to the Enlightenment-era conversation piece ideal than the work of any other twentieth-century artist.