(August 10, 1848 – October 29, 1892)

Born in Clonakilty, Ireland, in 1848, William Michael Harnett was brought to Philadelphia as an infant by his immigrant parents, a shoemaker and a seamstress. After several years of Catholic schooling, he began to contribute to his family’s support by selling newspapers and working as an errand boy. During his teenage years, Harnett trained as an engraver; by 1866 he was enrolled in the Antique class of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He continued his lengthy artistic education in New York, where he moved in 1869. While working in a silver engraving shop he attended classes at the Cooper Union and, for four years, at the National Academy of Design. He also sought instruction from the portraitist Thomas Jensen, but his time with that painter appears to have been brief.

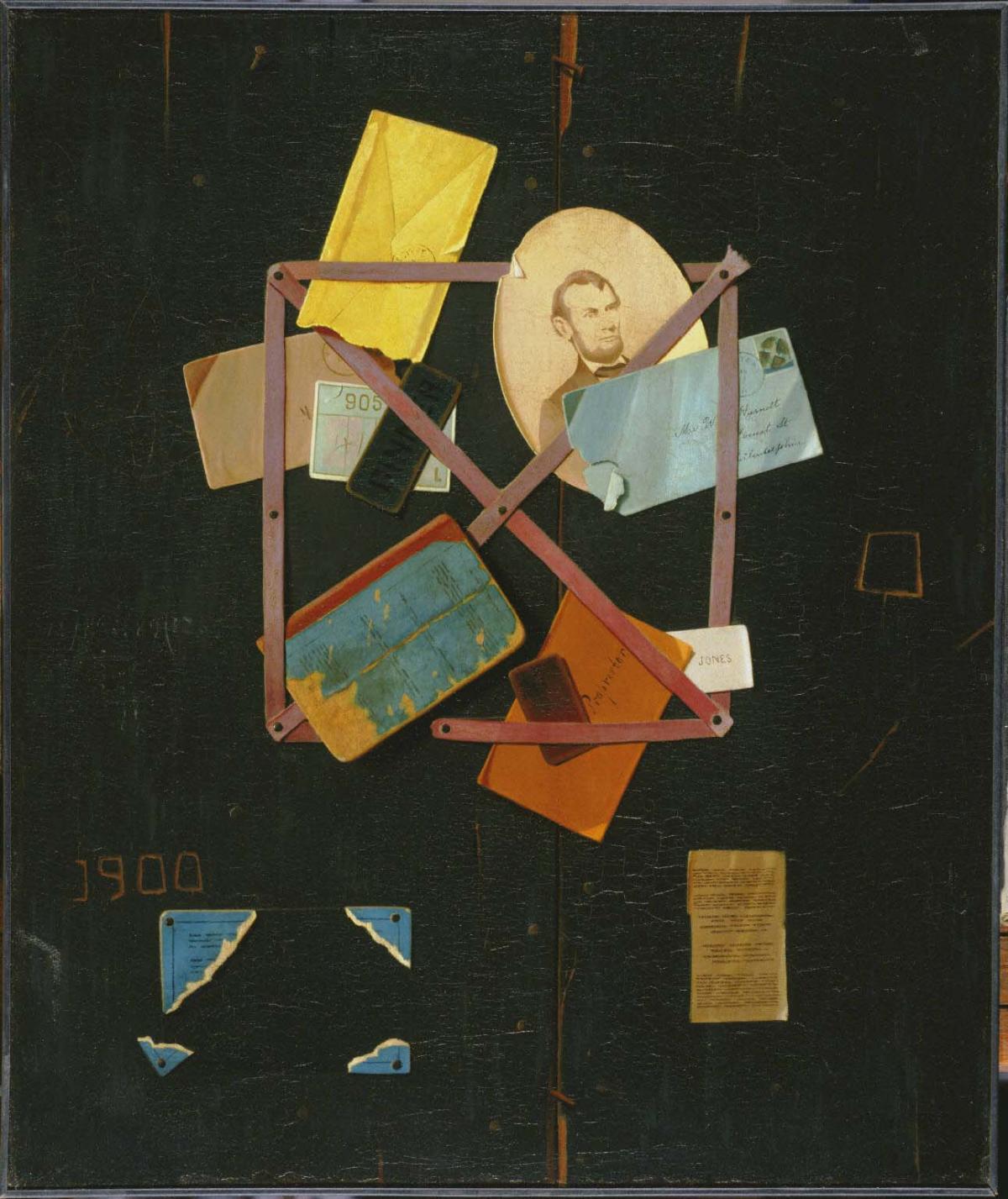

By 1875 Harnett had begun to execute oil paintings. That year he exhibited several fruit still lifes at the National Academy and the Brooklyn Art Association. A year later he was back in Philadelphia, exhibiting and, once again, studying at the Pennsylvania Academy. Harnett’s style of precise still-life painting changed very little throughout his career. Generally, he composed small groups of darkly toned objects (often materials associated with writing, reading, banking, drinking, or smoking) on shallow tabletops, paying particular attention to the intense description of surface texture. Later, his arrangements would grow more elaborate, with the introduction of time-worn objects from his collection of artistic bric-a-brac. Harnett’s effects of trompe l’oeil verisimilitude were particularly striking when he adopted an alternate compositional format of a shallow, vertical plane–usually a wooden door–from which letters, horseshoes, books, musical instruments, or wild game were suspended.

A sale of his paintings in 1880 provided the artist with funds to go abroad. After a brief stay in London and six months of employment for a private patron in Frankfort, Harnett settled in Munich, where he remained for about three years. During this period, he frequently sent canvases back to the United States for exhibition and sale. He was also active in the Munich Kunstverein, although his application to attend the Munich Royal Academy was rejected. The European sojourn ended with a short stay in Paris before his return to New York in 1886.

Harnett’s late years were marked by greatly expanded commercial success, but also by increasingly debilitating bouts of illness. His larger works now brought prices of several thousand dollars, and his uncanny naturalism found wide appeal among newspaper writers and general viewers. Although relegated to the margins of the professional artistic community (he was never elected to the National Academy), his influence was great among late nineteenth-century still-life painters. Yet rheumatism and kidney disease often kept him from his easel for periods of several months. Harnett sought relief from his condition–in Hot Springs, Arkansas in late 1887 and in Wiesbaden, Germany in 1889–and was forced to check into New York City hospitals on at least four occasions. He died in New York Hospital in 1892.