(September 12, 1898 – March 14, 1969)

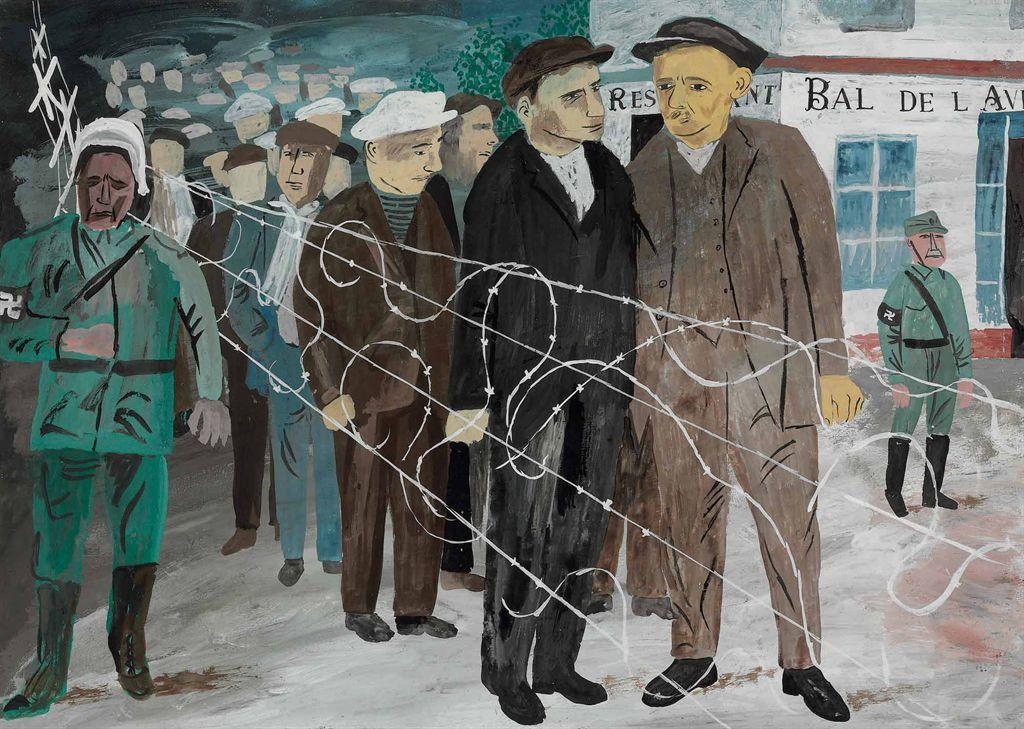

Ben Shahn was an American artist. He is best known for his works of social realism, his left-wing political views, and his series of lectures published as The Shape of Content.

Shahn was born in Kaunas, Lithuania, then part of the Russian Empire, to Jewish parents Joshua Hessel and Gittel (Lieberman) Shan. His father was exiled to Siberia for possible revolutionary activities in 1902, at which point Shahn, his mother, and two younger siblings moved to Vilkomir (Ukmergė). In 1906, the family immigrated to the United States where they rejoined Hessel, a carpenter, who had fled Siberia and emigrated to the US by way of South Africa.[1] They settled in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York, where two more siblings were born. His younger brother drowned at age 17. Shahn began his path to becoming an artist in New York, where he was first trained as a lithographer. Shahn’s early experiences with lithography and graphic design are apparent in his later prints and paintings which often include the combination of text and image. Shahn’s primary medium was egg tempera, popular among social realists.

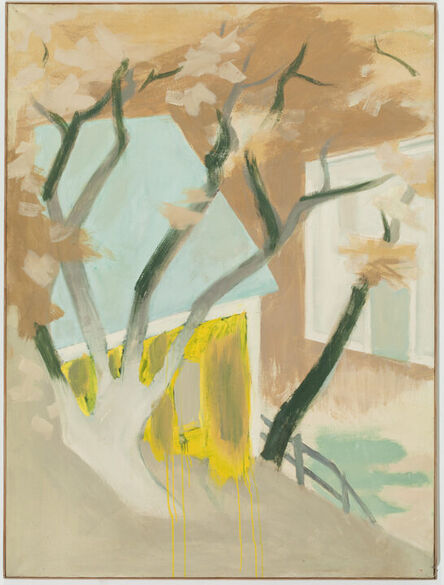

Although Shahn attended New York University as a biology student in 1919, he went on to pursue art at City College in 1921 and then at the National Academy of Design. After his marriage to Tillie Goldstein in 1924, the two traveled through North Africa and then to Europe, where he made “the traditional artist pilgrimage.” There he studied great European artists such as Henri Matisse, Raoul Dufy, Georges Rouault, Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee. Contemporaries who would make a profound impact on Shahn’s work and career include artists Walker Evans, Diego Rivera and Jean Charlot.

Shahn was dissatisfied with the work inspired by his travels, claiming that the pieces were unoriginal. He eventually outgrew his pursuit of European modern art, and redirected his efforts toward a realist style which he used to contribute to social dialogue.

The 23 gouache paintings of the trials of Sacco and Vanzetti communicated the political concerns of his time, rejecting academic prescriptions for subject matter. The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti was exhibited in 1932 and received acclaim from both the public and critics. This series gave Shahn the confidence to cultivate his personal style, regardless of society’s art standards.